Throughout ancient times the southern extreme of the Arabah Valley was–and still is–a very desolate region, yet this land was home to two extremely productive wealth generators for King Solomon’s lucrative domain. Solomon had inherited the southern Arabah from his father David, who had subdued Edom during his reign and gained control over the region (2 Samuel 8:13-14). Solomon then capitalized on his unfettered access to the Red Sea by launching a fleet of trading ships from Ezion-geber. These ships would return every few years loaded with immense riches and exotic goods from faraway lands (1 Kings 9:26-28; 2 Chronicles 8:17-18; 9:21). Later King Jehoshaphat attempted to do the same, but his ships met with disaster before they were ever able to set sail (1 Kings 22:48-49; 2 Chronicles 20:35-37). Likewise, recent archaeology has concluded that the great copper mines of Timna, located about 17 miles (28 km) north of the Red Sea, likely produced vast wealth for Solomon during his long reign. Originally controlled and worked by Egypt for over a thousand years, this sprawling mining center eventually came under the control of Solomon, who also controlled the highly productive copper mines at Punon further north in the Arabah. Over 10,000 mine shafts and tunnels have been found throughout the Timna region, and research suggests that Solomon’s reign marked the peak era of Timna’s productivity. While the mines were still under Egyptian control a temple was built on the site to honor Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of love and patron goddess of miners. Timna has also been suggested as a possible location where the Israelites crossed the Red Sea immediately after their exodus from Egypt.

The Near East during the Time of the Maccabees

After Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., his empire was divided among his generals, including Ptolemy and Seleucus. Initially the land of Israel came under the rule of Ptolemy, but by 200 B.C. it had fallen under Seleucid control. The Seleucid Empire originally controlled all of Alexander’s domain east of the Mediterranean coast except for Israel, but over time the Parthians broke away and established their own empire. At the same time the Roman Empire was expanding its rule across the Mediterranean world as well. These increasing threats surrounding the Seleucid Empire led Antiochus IV Epiphanes to impose a strict policy of hellenization through his empire, likely in an effort to solidify power over his diverse domain. Non-hellenistic religious practices such as circumcision and Sabbath observance were forbidden, pagan practices such as sacrificing swine and eating pork were mandated, and copies of the Hebrew scriptures were banned and destroyed (1 Maccabees 1; 2 Maccabees 6-7). Eventually the harsh policies of Antiochus IV fomented open rebellion by faithful Jews under the leadership of Mattathias Maccabeus and his sons in 167 B.C., who established a largely independent kingdom over the land of Israel (1 Maccabees 2; 2 Maccabees 8). The Romans eventually affirmed an alliance with the Maccabean leaders and encouraged other nations in the region to do the same. The map shown here displays this complex political world of the Near East around 90 B.C., shortly before the Romans absorbed the Seleucid Empire and the Maccabean Kingdom in 63 B.C.

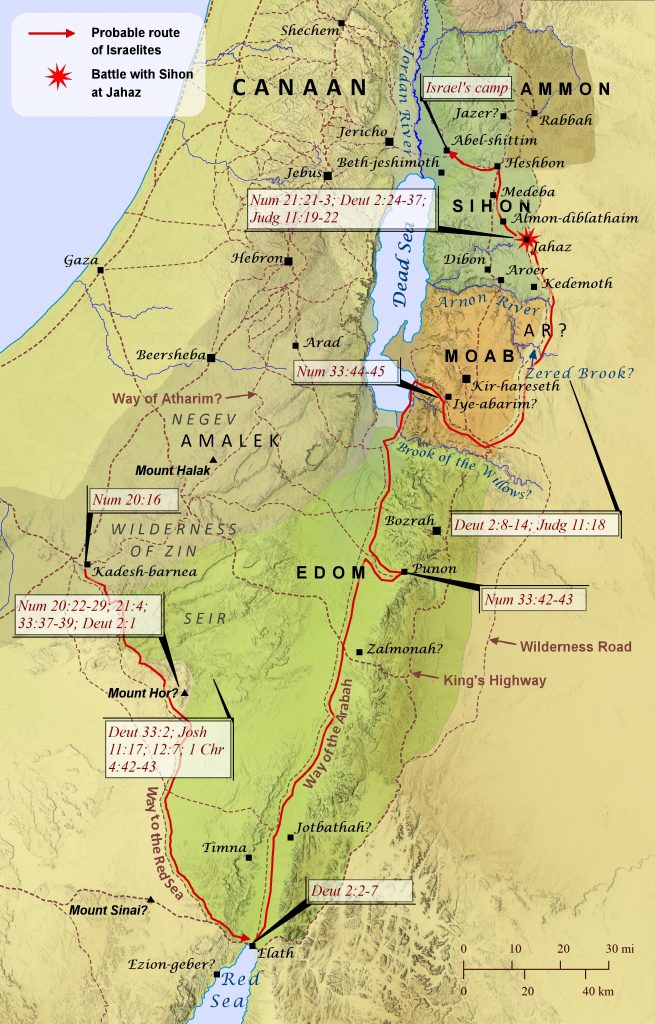

The Journey to Abel-Shittim

Numbers 20:14-21:20; 33:37-49; Deuteronomy 2:1-23; Judges 11:14-27

Four separate passages of Scripture recount the Israelites’ journey from Kadesh-barnea to Abel-shittim, yet precisely tracing this route on a map is surprisingly difficult. Most of the specific locations mentioned are either unidentified or uncertain, and some comments about the journey can seem difficult to reconcile with other comments. Yet the relevant passages provide enough geographical markers that can be identified with reasonable confidence to make it possible to reconstruct what was likely the route they took to Abel-shittim (shown here). From its earliest days, Edom controlled the area known as Seir, southeast of Kadesh-barnea (see Deuteronomy 33:2; Joshua 11:17; 12:7; 1 Chronicles 4:42-43), which is why the Israelites told the king of Edom that they were on the edge of his territory while they were still at Kadesh-barnea (Numbers 20:16). When the king of Edom refused their request to pass through his land, Israel turned back (Numbers 20:21; Deuteronomy 2:1) and apparently headed southeast, skirting the Edomite land of Seir. Two passages mention Mount Hor, where Aaron died, as one of the first stages on the Israelites’ journey (Numbers 21:4; 33:37), but it is unclear where this mountain was located. A popular tradition locates it about 22 miles (35 km) south of Punon at Jebel Harun, but this location is too far from Kadesh-barnea to be one of the first stops on their journey, and at this time it was in the middle of Edom’s territory rather than on the edge of it, as both passages imply. Any candidate for Mount Hor must have been southeast of Kadesh-barnea, since Israel “turned back” to begin their journey, and Har Karkom (as shown here) fits these requirements. Then, in an apparent shift from earlier, Israel passed through Edom (Numbers 33:42-43; Deuteronomy 2:2-6) and turned from the Way of the Arabah to camp at Iye-abarim. The town of Iye-abarim was most likely located at Khirbat `Aiy, as shown on this map, for several reasons. To begin with, the predicate “-abarim” before “Iye” likely indicates that it was situated among the Abarim Mountains, which ran along the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. Also, Numbers 33:44 notes that Iye-abarim was located “in the territory of Moab,” though the Israelites were ultimately making their way to the Wilderness Road outside the bounds of Moab (Deuteronomy 2:8; Judges 11:18). Finally, the Medeba Map clearly identifies a town named Ai (a variant spelling of Iye) at the exact location of Khirbat `Aiy.[see footnote] Then, after passing Moab on the east along the Wilderness Road, the Israelites camped in the Zered Valley (likely the Wadi e-Tarfawiya as shown here and not the Wadi al-Hasa, which was likely the Brook of the Willows mentioned in Isaiah 15:7), and then they camped again on the other side of Arnon River (Numbers 21:11-12; 33:44-45). Then the Israelites sent messengers to Sihon, asking permission to pass through his land (Numbers 21:21-22; Deuteronomy 2:24-29; Judges 11:19). Years earlier Sihon had taken the land north of the Arnon River from the Moabites (Numbers 21:26), which explains why this area was still referred to as Moab at times (e.g., the plains of Moab). The region also appears to have been claimed by the Ammonites as well (Judges 11:13), though it is not clear whether they ever actually controlled it. Sihon refused to allow the Israelites permission and instead attacked them at Jahaz, but the Israelites defeated him and took his land for themselves (Numbers 21:23-31; Deuteronomy 2:30-36; Judges 11:20-22). Then they set up camp at Abel-shittim and prepared to enter the Promised Land of Canaan (Numbers 33:48-49).

[footnote: Though virtually all translations understand Numbers 21:11 as placing Iye-abarim in the wilderness that is east of Moab, this author is convinced that it is saying instead that Iye-abarim is in the wilderness that faces (Hebrew panim) Moab when looking eastward. Other examples of the use of the word faces to place something in a non-eastern position relative to another object by indicating the point of view of the reader include Joshua 13:24-25 (Gad’s boundary could not have included a town that was east of Rabbah) and Joshua 18:14 (it seems to make the most sense that the hill in view is probably the prominent hill to the north of Beth-horon–that is, before it when looking southward).]

Gedaliah Is Assassinated

2 Kings 25; Jeremiah 40-44

Sometime after the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and exiled the upper echelons of Judean society to Babylon, they appointed a Judean named Gedaliah as governor over those who remained in the land. At Mizpah Gedaliah encouraged those who remained to embrace Babylonian rule and reestablish their lives in the land, cultivating the land and harvesting crops as they had before. Many Judeans who had fled to neighboring lands heard about this and returned to Judah as well. Among them was a man named Ishmael, a member of the Judean royal family who had been one of the king’s officers. Another officer named Johanan warned Gedaliah that Ishmael had been sent by the king of Ammon to kill Gedaliah, but Gedaliah did not believe him. Eventually Ishmael came to Mizpah with ten other men and killed Gedaliah and all the Judeans and Babylonian soldiers who were there. The next day, eighty men from Shechem, Shiloh, and Samaria were traveling to the Temple of the Lord to make an offering, and Ishmael went out and invited them to stop at Mizpah. But after they entered the city, Ishmael and his men slaughtered many of them and took the others captive. He set out with them to escape to Ammon, but by this time Johanan and the other officers had heard about what had happened and pursued Ishmael, forcing him to turn back toward Gibeon. There Johanan and his men caught up with Ishmael and freed those taken captive, but Ishmael and eight of his men escaped to Ammon. After this Johanan, his officers, and all those he had recovered set out for Egypt, because they feared what the Babylonians would do when they learned that Ishmael assassinated the governor they had appointed. Along the way the Judeans stopped near Bethlehem and consulted Jeremiah, asking him whether they should flee to Egypt. After ten days Jeremiah told the Judeans that they should not go to Egypt and that those who did so would die or suffer hunger there. But Johanan and the other leaders refused to heed Jeremiah’s warning and took everyone–including Jeremiah–with them to Egypt, traveling as far as Tahpanhes. There the Lord told Jeremiah to prophesy that the Babylonians would one day seize the land of Egypt as well. Jeremiah also prophesied against Judeans who had fled to other parts of Egypt, including those in Migdol, Memphis, and Upper Egypt much further south (Jeremiah 44:1).

Border Conflict between Israel and Judah

1 Kings 15:9-22; 2 Chronicles 16:1-6

Around 895 B.C., a few decades after Israel divided into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah, a border dispute erupted between the two nations. King Baasha of Israel seized the strategic Judean border town of Ramah and fortified it to gain control over all routes leading to and from Judah along its northern border. King Asa of Judah responded by bribing Beh-hadad I, king of Aram, with all the silver and gold that remained in the treasuries of the Temple and his own palace. Ben-hadad accepted Asa’s bribe and attacked Israel, capturing Ijon, Dan, Abel-beth-maacah, the area of Kinnereth, and all Naphtali. After this Baasha stopped building Ramah and withdraw to his capital city of Tirzah, and Asa ordered everyone in Judah to carry away the stones and timber from Ramah. Asa then used the materials to build up Geba and Mizpah, thereby moving the border further north and ensuring a watchful presence over key routes heading north and east. The Bible is unclear how long Aram retained control over the region of Naphtali. Years later King Ahab of Israel waged several more battles with the Arameans (1 Kings 20-22; 2 Kings 6:24-33), and he may have recovered Naphtali during that time.