2 Kings 2

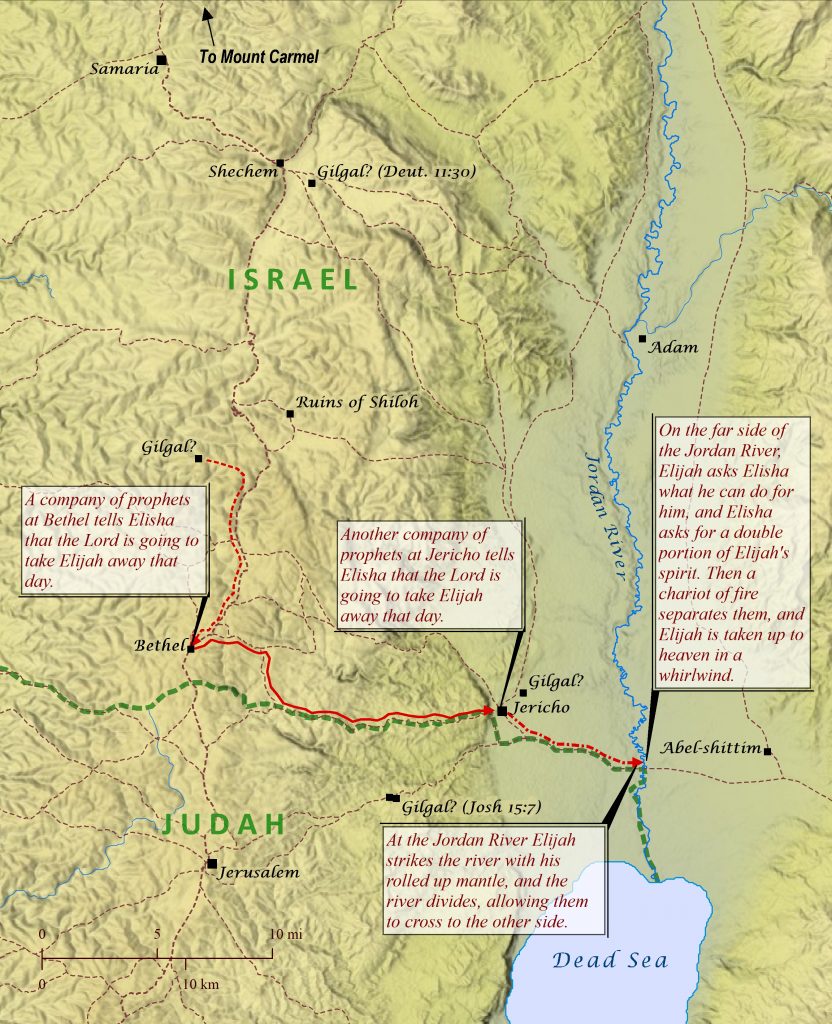

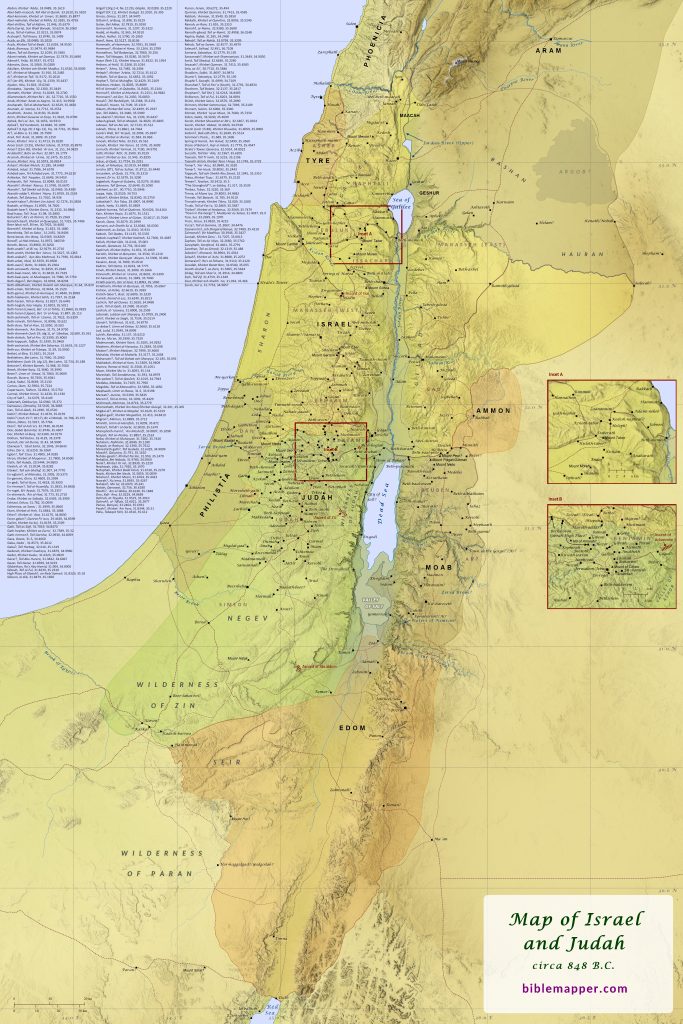

The famous story of the prophet Elijah being carried to heaven in a whirlwind begins with Elijah and Elisha at a place called Gilgal. The term Gilgal, meaning “circle of stones,” is used to reference at least three locations throughout Scripture (see Joshua 4:19; 15:7; 2 Kings 2:1) and perhaps a fourth location (Deuteronomy 11:30). It is unlikely that the Gilgal mentioned in this story was the one in the immediate vicinity of Jericho, where the Israelites first camped after entering the Promised Land, nor is it likely that it was the one mentioned in Joshua 15:7, which marked part of the border of Benjamin’s territory. It is possible that the Gilgal of the Elijah and Elisha stories was the same Gilgal mentioned in Deuteronomy 11:30, which must have been opposite Shechem, but it is more likely that it was located instead at modern Gilgilia in the hill country of Ephraim, as shown on this map. The story then recounts that Elijah and Elisha traveled to Bethel, where a group of prophets asked Elisha if he realized the Lord was going to take his master away that day. Then Elijah and Elisha continued on to Jericho, where another group of prophets asked Elisha the same thing. Finally, Elijah and Elisha went to the Jordan River, and Elijah rolled up his mantle and struck the water with it. The river parted, just as it did for the Israelites when they first entered the Promised Land (Joshua 3), and the two prophets crossed to the other side on dry ground. There Elijah asked Elisha what he could do for him before he was taken away from him, and Elisha asked for a double portion of Elijah’s spirit. As they were walking and talking, a chariot of fire appeared and parted them, and Elijah was taken up to heaven in a whirlwind. Elisha then picked up Elijah’s mantle and began his own ministry by striking the Jordan River with it again and parting the waters for him to cross.