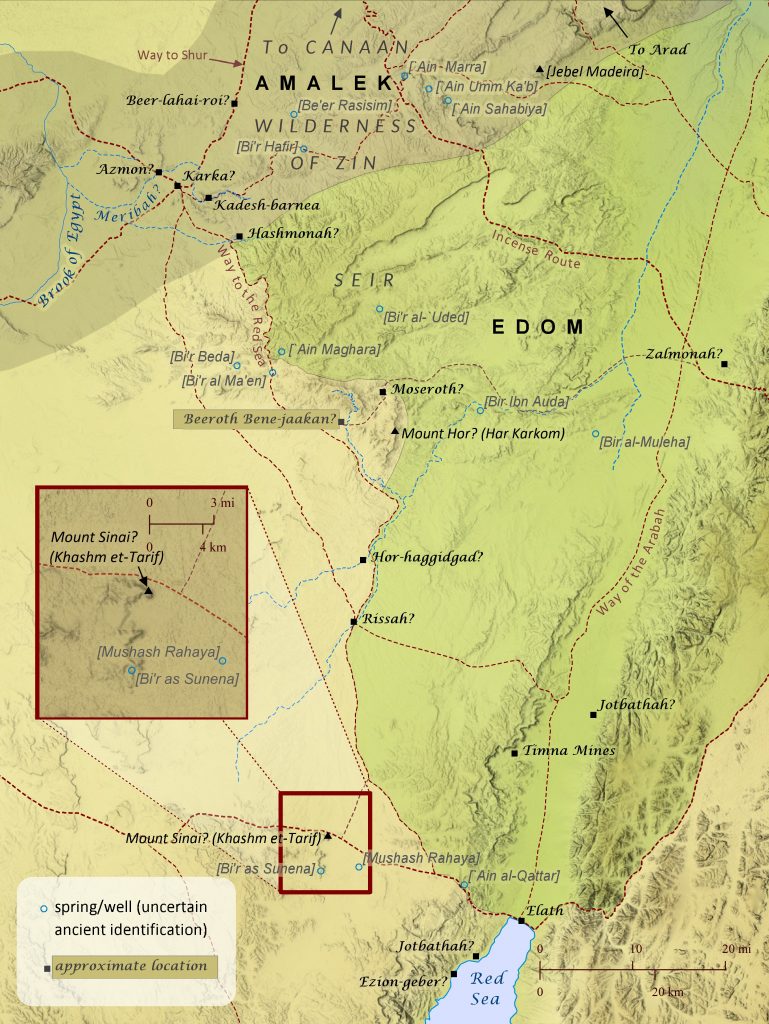

Numbers 13-14; 20-21; 33; Deuteronomy 1-2; 10:6-9

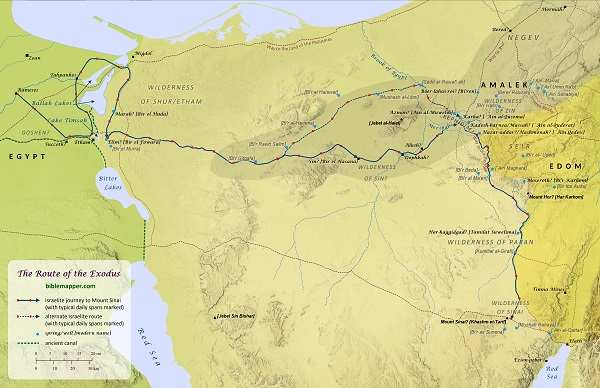

After the Israelites received the law on Mount Sinai, which may have been located at Khashm et-Tarif (see also “The Route of the Exodus”), they traveled to Kadesh-barnea, a distance that took eleven days “by the way of Mount Seir” (Deuteronomy 1:2). The phrase “by the way of Mount Seir” suggests that more than one route existed between Mount Sinai and Kadesh, as shown here, but the road the Israelites took probably ran alongside the mountainous region of Seir. This route would have offered greater access to water from wells, natural springs, and seasonal streams flowing from the hills of Seir–a critical necessity for a large group traveling through this very arid region. Nearly every location identified on this map was essentially a small community centered around one of these life-enabling sources of water. After reaching Kadesh in the wilderness of Zin, the Israelites prepared to enter Canaan by sending spies to scout out the land. But when ten of the twelve spies brought back news about the strength of the Canaanites, the people became afraid to enter the land, so the Lord punished them by condemning them to travel in the wilderness for forty years until that generation died off. Some Israelites repented and tried to enter the land, but they were beaten back to Hormah by the Amalekites and Canaanites. So for forty years the Israelites traveled from place to place, probably in the general area of Kadesh-barnea, though very few locations mentioned are able to be established with much certainty. As the forty years of traveling drew to a close, the Israelites prepared again to travel to Canaan by requesting permission from the king of Edom to pass through his land. When the king refused, the Israelites “turned away” from the Edomites and set out from Kadesh to travel to Mount Hor. The Jewish historian Josephus located Mount Hor at Jebel Nebi Harun, a very tall mountain in eastern Edom, but this has been rejected by many scholars in favor of other sites such as Jebel Madeira to the northeast of Kadesh. This author is convinced, however, that any candidate for Mount Hor must be sought to the south of Kadesh-barnea. Numbers 33:30 and Deuteronomy 10:6 mention that, during their wilderness travels, the Israelites camped at Moseroth/Moserah, which was apparently located at Mount Hor, since both Moseroth/Moserah and Mount Hor are cited as the place where Aaron died (Numbers 21:29-29; 33:37-39; Deuteronomy 10:6-9). It is difficult to envision the Israelites traveling back to the edge of Canaan after suffering defeat there the last time they attempted to enter the land. These same passages also note that after their stay at Moseroth/Moserah the Israelites traveled to Hor-haggidgad/Gudgodah (probably located along the Wadi Khadakhid) and then to Jotbathah, with no mention of passing through Kadesh, which they would have had to do if Mount Hor was north of Kadesh (since they were avoiding the land of Edom). Also, in Deuteronomy 2:1 Moses says that after the Israelites left Kadesh, “we journeyed back into the wilderness, in the direction of the Red Sea, as the Lord had told me and skirted Mount Seir for many days,” and Aaron’s death on Mount Hor fits best during this time. Similarly, Numbers 21:4 says “from Mount Hor they set out by the way to the Red Sea, to go around the land of Edom,” but there would have been no way to the Red Sea around the land of Edom if Mount Hor were located northeast of Kadesh. One element of the wilderness narratives that appears to favor a northeast location for Mount Hor, however, is the story of the king of Arad, which the book of Numbers (chapters 21 and 33) places immediately after the death of Aaron on Mount Hor. At first glance, the narrative seems to imply that the king attacked the Israelites at Mount Hor, which fits better with a northern location. Yet, it is also possible that the story is simply noting that it was after the Israelites’ arrival at Mount Hor that the king of Arad first learned of the Israelites’ renewed intentions to enter Canaan, perhaps as a result of their request to pass through Edom. But it may have been later that the king of Arad actually engaged them in battle, perhaps as they were passing north of Zalmonah and appeared to be ready to enter Canaan by way of Arad (see Numbers 33:41-42 and the map “The Journey to Abel-shittim”). For these reasons, this author believes that Har Karkom is the best candidate for the location of Mount Hor. The site is appropriately located at the edge of Seir and along the way to the Red Sea. This site’s role as an ancient cultic center is also well established. Perhaps Aaron’s priestly duties and authority in Israel had grown out of a similar role he had previously held at Mount Hor (see also Numbers 12:1-2; Deuteronomy 33:2; Judges 5:4-5), where he was eventually buried.